By Shuli Karkowsky, Moving Traditions CEO

Today is Yom Hashoah – Holocaust Remembrance Day. Many of us are watching with trepidation the rise in antisemitism, reports from college campuses that protestors are telling Jews to “go back to Poland” (however isolated those incidents may or may not be), the comparisons of campus vandalism to Kristallnacht. Many of us are scared. And because the Holocaust is one of the only incontrovertible instances of unmediated evil that people can point to, it has become a reference point, an important rhetorical device used by both the right and the left. And while I understand the pull of those comparisons, it is important to me on Yom Hashoah not to use the day to make a point, but to remember. Because the Holocaust is not an abstract rhetorical tool – it’s our communal history. And for me, personally, it is my family’s story.

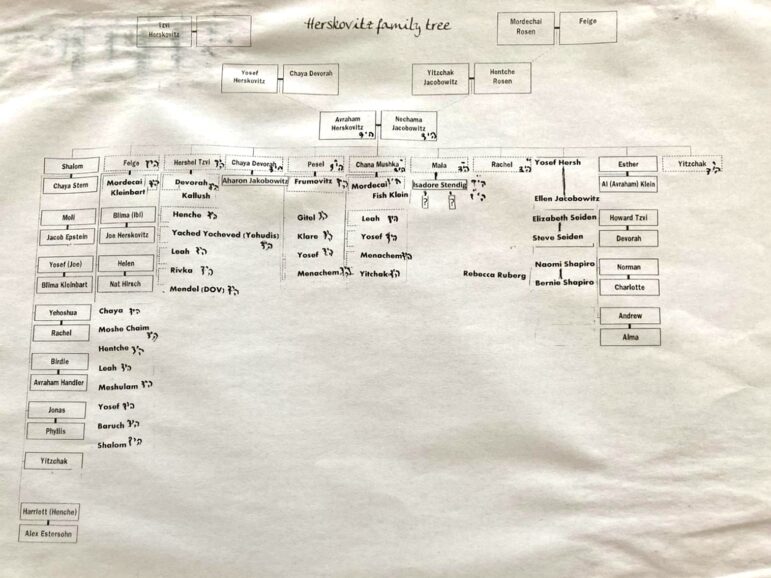

Every Yom Hashoah, I look at my grandmother’s family tree. Next to many of the names, you’ll see two Hebrew letters ה”ד which each carry an unspeakable tragedy. They stand for “Hashem Yikom Damam,” or “God should avenge their bloodshed,” an indication that person was killed by the Nazis. It appears dozens of times on just this small snippet of my mother’s family tree. My grandmother – known as Blima, Ibi, and Bea as she survived through each transition of her horrific life – is the first child of Mordechai and Feige, the second branch from the left.

For me, the tree marks a universe of death for entire generations. My grandmother’s mother and father perished, along with 7 of her aunts and uncles. In the next generation, my grandmother lost 8 of her 9 siblings in the Holocaust, all of whom were younger than she was at the time (a teenager). She survived the concentration camps with her sister Helen, and her aunt, Esther, who was similar in age despite being her aunt. The rest of the family they knew disappeared in those war years.

Even when I look at this tree, I can feel how easy it is for the Holocaust to become an abstraction. My grandmother hated telling her Holocaust story. It would bring on nightmares; there was no version she could think of that was appropriate for children to hear. Until her death, eighty-two years after she was liberated from Auschwitz, she could not walk down steps into basements, the dark windowless corridors reminding her immediately of the walks toward slave labor and death that she and her siblings took.

With that said, we have been careful to preserve the snippets of my family’s story that my grandmother told – through official documenting channels and through family lore.

My grandmother and her family were rounded up from their home in Seredne, Czechoslavakia on the second night of Passover – an intentional and cruel choice by the Nazis to disrupt a Jewish tradition celebrating freedom from oppression. My grandmother and her nine siblings were put in a cattle car packed like animals. There was no food, water, or bathrooms provided for the multiday trip. The cattle car quickly stank of both feces and death. She remembers her mother grabbing raspberry syrup – one of the few shelf stable staples they had that was kosher for Passover – in the hopes that there would be water to pour it into and perhaps make my grandmother’s six-month-old brother something he could drink on an interminable journey filled with dying people and their refuse. Once they arrived at Auschwitz, my grandmother was sorted to the right for labor while her mother and eight of her younger siblings were sorted to the left, for death. She never saw them again.

I heard the story of their round-up for the first time nine years ago, when my own twins were just about six months old, right around Passover. For hours, I was paralyzed by the thought: what would I do, what would I take, if my family was taken in that moment? I still can’t unpack my Passover foods and dishes without that moment of paralysis: what happens if I ever have to make those choices? The memory is not an abstraction – it is both inherited trauma and an eternal lesson for posterity.

We can take many lessons from the Holocaust. Some of us learn that antisemitism will never go away, that we must forever be diligently on watch for the flare of hate that means death for our people. Some of us learn that ordinary people often participate in evil – that mob mentalities can lead people to justify true atrocity. Some of us learn that “Never Again” means we can never allow Jewish lives to be threatened just for being Jewish. Some of us learn that “Never Again” means that we must be vigilant to stand up the lives of any people who are threatened for who they are, as my ancestors wish the world had stood up for them.

None of these lessons are mutually exclusive. All of them are valuable. And today is the day to recognize that all of them are lost if we allow the Holocaust to become a mere abstraction.